Oscilloscope Firmware Update

Saturday, July 29th, 2023

It may appear at the start of his story that this is an unhappy tale, but bear with it, there is a happy ending.

Having an oscilloscope when working with electronics is a must even for hobbyists. The amount of information you can gather about the behaviour of a circuit is invaluable. The daily workhorse here is the Rigol MSO5104 Mixed Signal Oscilloscope.

This scope is really a small computer and like all computers a regular check for firmware updates is always a good idea. A recent visit to the Rigol web site resulted in a new firmware version downloaded to the laptop.

Time to Install

Installation should be a quick process:

- Extract the files on the PC

- Copy the firmware file (.gel file) to a USB drive

- Connect the USB drive to the oscilloscope and select Local Update from the System menu

Following the process resulted in the update dialog being shown with a progress bar followed by instructions to restart the oscilloscope.

Power cycling the oscilloscope presented the expected Rigol logo along with a progress bar, so far, so good. The boot continued until just before the end of the process bar and then it stopped.

Wait a little while longer.

No movement after 5 minutes, time to power cycle. The same thing happened. Rinse and repeat, still no progress.

Time to call the local distributor.

Recovery

A call to the local Rigol distributor in the UK was in order. I found their technical support really good. In fact it was FAN-TAS-TIC. The solution turned out to be fairly simple.

- Power off the oscilloscope

- Turn the oscilloscope on again

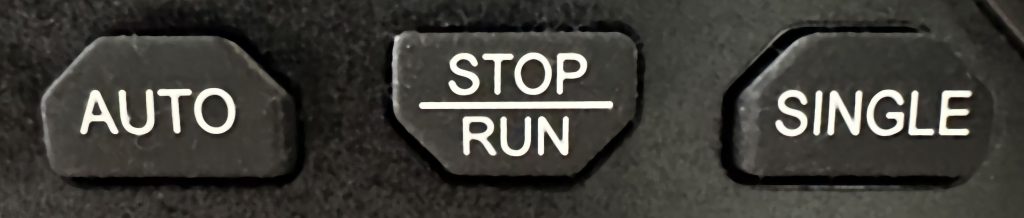

- As the oscilloscope starts press the Single button repeatedly

Doing this would eventually show the Rigol logon on the screen with two options:

- Upgrade Firmware

- Recover Defaults

Selecting Recover Defaults took us through the recovery process and after a few minutes restoring the configuration and restarting the oscilloscope it was back up and running again.

Conclusion

Computers are all around us running in everything including the modern oscilloscope. Rigol has thoughtfully added a recovery mechanism into the firmware update process and so today all was not lost.

A call out to the UK distributors, the support was really, really good.